Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act prohibits employers from discriminating against employees on the basis of several things, among them race. The law, however, doesn't define "race."

It also doesn't say anything about hair.

Which brings us to Chastity Jones.

Jones was offered a job in the customer service department at Catastrophe Management Solutions, a claims-processing company in Mobile, Ala. But there was a catch: During the interview, CMS's human resources manager told Jones that the company could not hire her "with the dreadlocks," which were against company policy.

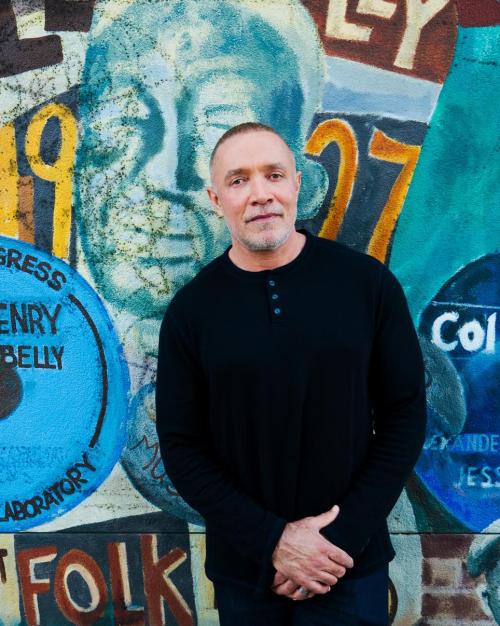

Noliwe Rooks, a professor of Africana and gender studies at Cornell University, often writes about the nexus of beauty and race. While many companies have what appear to be race-neutral grooming policies, Rooks said, the enforcement of those policies often can be affected by how employers think of race.

"I have yet to come across an actual court case ... and it's overwhelmingly black people that this is adjudicated around ... where the texture of hair for another racial group has reached the point of a court case," Rooks said.

The sticking point in Jones' lawsuit or the many other cases that have been litigated, she said, is management.

"The supervisors are generally white and they often say, 'I'm not used to hair like that,' " Rooks said. It is, she says, an individual decision that the company trusts supervisors to make in the interests of the company's public image. "Corporate America is not comfortable with certain types of hairstyles that are generally associated with black people," Rooks said.

She cited a case in the San Francisco Bay Area, where a young black man worked in the mailroom of a national corporation and was told to lose his dreadlocks. "He was working with people who had Mohawks, pink hair, piercings, tattoos," Rooks said. "But he alone was singled out and told he needed to change his hair because his hair did not fit with the rules around appearance, hair length, hairstyle."

But his new school demanded that all boys have short hair 'to teach hygiene, instill discipline, prevent disruption, avoid safety hazards and assert authority.'

The hair issue is not exclusively about black people. Native American men, for example, have fought for more than a century for the right to keep their hair long. In 2008, Adriél Arocha was barred from attending school in Needleville, Texas, unless he cut his hair. Adriél was a 5-year-old Lipan Apache. His parents considered his hair to be an outward manifestation of his heritage and religion. Men in his tribe only cut their hair after life-changing events, such as the death of a loved one. But his new school demanded that allboys have short hair "to teach hygiene, instill discipline, prevent disruption, avoid safety hazards and assert authority," according to the suit his parents filed against the school district.

The 5th Circuit Court of Appeals said the request that Adriél pin up or hide his hair "offends a sincere religious belief" and affirmed a lower court's decision in Adriél's favor.

While some African-Americans have cited similar religious arguments for wearing dreadlocks (Rastafarians, for example), Cornell's Rooks said that many feel their hair is a form of self-expression and cultural affirmation — which may be just fine until it bumps into a corporation's desire to express itself.

Read the full article on NPR (article edited for length and clarity in above reproduction).