Dear Graduate Students and Colleagues:

It is not too hard to imagine that the last three months have been stressful for many of us. First came the coronavirus pandemic. The pandemic did not just disrupt our classes and compel us to embrace unproven modes of teaching. The pandemic also altered how we live by causing us to separate from one another; to shelter at home for lengthy periods of time; and, frankly, to lose crucial dimensions of social life, including the pleasure that many of get from face to face encounters, the touch of another, and the ability to commune in the many forms of public squares available to us.

Cornell University recognizes this new reality and has sought to assist undergraduate and graduate students in adapting. You have all gotten a slew of emails from the school with links to helpful resources. The University has also tried to figure out ways to repurpose existing resources to meet the emergent needs of graduate students. I trust that you will all turn to them when required. You may also call on the DGS and the staff of Africana studies to help you in accessing the available resources when necessary. The university, the teaching personnel, and our department are all fully aware that the pandemic will affect the progress of a great many graduate students, including foreign students and those with research projects abroad. In fact, even ordinarily simple tasks like taking exams have become complicated and stressful.

Anti-black racism already textured many of the challenges of the pandemic in this country. Black people remain more likely to contract and die from the virus than other groups. But the lynching of George Floyd has brought the reality of anti-black racism to the forefront of our minds and our politics. We will talk about this latter matter at a town hall meeting shortly (date & time will be sent soon). Floyd’s murder and the questions and issues that it has brought to light (and life) in our public discourses, politics, and relationships have thrown many into internal turmoil of rightful anger and legitimate questions about the endurance of racism in the US spanning slavery, the civil war, the postwar constitutional amendment, the Brown decision by the Supreme Court, the civil rights movement, the passage of the voting rights act and the attempted school and housing integrations that ensued, and of course, the growth of mass incarceration and intensification of (often violent) police forces among black communities throughout the country. You all know this already, I am sure. But many people are learning these things for the first time. They may not grasp (or care) why you are so mad at and disheartened by the situation. And this lack of understanding can often be even more maddening and disheartening.

I urge you, first of all, to take care of yourselves. Taking care of the self may mean many things. It may mean setting aside ordinary tasks to reflect and work through your emotions and questions. You should if the situation beckons such attitude. There will be time to return to routine tasks and, as I have said, the University, the department, and individual faculty are understanding. It is healthy and necessary, Kpelles of the rainforest of Guinea say, to feel pain, and admit to weakness and helplessness that pain brings with it.

But the moment will also come when we will need to think beyond the moment. It is also responsible and indispensable to think about what steps to take after the fall. The tree trunk on which you stumbled is not the only one in the forest. There are many more to mind. The moral of the story is that it is never sufficient to say that I am hurt so much that I don’t want to think about what comes next. What comes next and what awaits us when this pain recedes is what I want to talk about. Again, the pain may be so acute that some of you may want to read the remainder of this message later. I encourage you only to read further when you feel ready.

The recent show of empathy and, at times, real support on the part of protesters have been at once confusing and heartening. Just a few years ago, majorities in the US might have cast the murder committed before our eyes as a random if criminal act by a rogue police officer. It is thus with relief that today individuals and social and political entities from all horizons seem to agree that the death of Mr. Floyd was institutionalized murder. Even more surprising, few today hesitate to link the practice that led to his death to the violence that the US had wrought on African-descended people.

The change of tone and attitude may not be sufficient to dispel questions that you may have about the moment upon us. The one question that comes naturally to me is whether the reforms envisaged by protesters, civil society organizations, and political parties would radically uproot institutionalized racism. For now, the focus seems to be on the police and policing. The fact is that institutionalized racism is structural and the violence that flows from it is institutional. The murderous actions of the police cannot therefore be cast as ‘mere’ derelictions of ‘rogue’ police agents.

This is a moment to reflect on our mission as Africana scholars. We must remember and act upon the fact that our fate as a people is inextricably linked to the support that we get from one another. I recall Malcolm X’s 1964 admonition to African leaders during his visit to the first annual meeting of the Organization of African Unity: that the entire Black World would be respected if Africans demand it. What is less known is the incident that underlay that realization. It was an incident in the suburbs of Washington in April 1961 when Dr. William H. Fitzjohn, Charge d ‘Affaires of Sierra Leone, went to a Howard Johnson for lunch and was refused service on account of his race. Dr. Fitzjohn not only insisted that he be served, he reportedly said that he wanted his order to be served with ‘a side of desegregation’. It is a diplomatic incident that reverberated in the halls of the United Nations, one that the young Kennedy Administration could not afford for geo-strategic reasons. That event, according to US official archives, more than Robert Kennedy’s prodding, brought Kennedy to the realization that he should support the civil rights movement (https://www.history.com/news/african-diplomat-segregation-scandal-jfk). On the third day after the murder of George Floyd, the president of Ghana, Nana-Akufo Addo reiterated the same point. We, as African-descended peoples, must be able to rely on each other’s support – and just solidarity. Dr. Fitzjohn, for example, learned his pan-African pride from generations of West Indians who spent careers in education and politics in Sierra Leone and Liberia.

Fanon was correct. ‘Each generation’ he proclaimed, ‘must, out of relative obscurity, discover its mission, fulfill it, or betray it’. We must decide today what mission our generation is going to take up and how to carry it forth. Anti-black racism is not limited to the United States. Around the world, modern anti-black racism reflects misguided responses to profound crises of society, institutions, morals, and legitimacy in nearly every society around the globe. It is not my intention to name the sources of theses crises. Still, it behooves us to name a few: a nascent version of predatory and extractive capitalism; the abandonment of republicanism and its predicate of universal and equal citizenship in favor of nativism in fiscally-pressed Western states; and the willingness of elites everywhere to instrumentalize democracy itself for political and material gains for the few at the expense of the many.

Of course, there are deep-seated institutional, cultural, and political forces behind anti-black racism that are unique to the US. But there is no doubt that these crises affect the African diasporas disproportionately regardless of contexts around the world. This reality places a special burden on those of us engaged in education. Indeed, there is an undeclared race currently underway to shape the future itself. This race involves education. Turning again to our precursors, I wish to remind us of the dictum by Frederick Douglass that ‘It is easier to build strong children than to repair broken men.’ There is very little that can be done with ill-willed and ill-educated grown-ups, of whom there are many in our politics, on television, and in what passes for public discourse nowadays. It is for this very reason that we must seize upon our mission as educators—students and teachers—to address the crises of society, institutions, morals, and legitimacy that are now upon us. Far be it from me to tell anyone what this mission should look like and what would be required to execute it. I can only surmise that both the mission and its execution would require revisiting the institutional practices of the academy as well as metaphysics, methods, and modes of inquiry through which our observations are filtered and upon which our analyses depend. These are the means by which the new regimes of truths, of facts, evidence, and proofs are generated to justify different visions of the future. Black scholars, thought, and institutions are already and must continue to be at the center of these efforts.

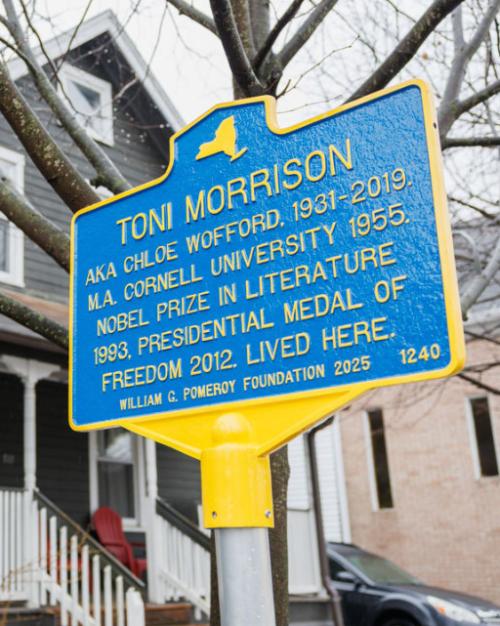

We have earned a space in the academy from which we can pursue our mission to, as Aimé Césaire put it, ‘humanize humanity’. May we then take the paths laid down for us by Frederick Douglass, W.E.B Dubois, Ida B. Wells, E.W. Blyden, Frantz Fanon, Angela Davis, Toni Morrison, Shirley Chisholm, and countless other precursors who sought in the African Diasporas the ability to change the world and mandated that we do so by opening ours and the minds and hearts of others to new possibilities.

Good luck to all of us because the road ahead is long and there may be many more trees on our paths. We do not know where they may be and how tall, small, heavy, light, straight, crooked or easy to remove they may be. But we can prepare to remove them.

Director, Graduate Studies

Africana Studies and Research Center.