The Society for the Humanities fall conference, “Performing Skin,” explored the year’s focal research theme: skin. Held Oct. 21 and 22 in the A.D. White House, the interdisciplinary conference reflected on philosophical, aesthetic, political, ecological, religious, psychoanalytical and cultural understandings of skin.

In his introduction, Timothy Murray, the Taylor Family Director of the Society for the Humanities, called on the audience “to think skin in relation to cultural horizons, religious traditions, flesh, haptics, signs, texts, images, biopolitics, screens, sounds and surfaces.” He noted that “from the earliest writings on medicine and religion to more recent theories of race, sexuality, gender, class and ethnicity, the society’s fellows are considering how thinking or making skin inform the global cultural experience.”

The plenary lecture was delivered by Debjani Ganguly, director of the Institute of the Humanities and Global Cultures at the University of Virginia. Her talk, “The Skin of the World: Allegories of Global Terror,” focused on “skin as threshold, as what is exposed and hidden.” Using novels as her primary texts, she discussed skin as metaphor, allegory and “in terms of regimes of violence and what they do to the skin and representations of the skin.”

In her talk on “Protest, Nudity and Universalism,” Naminata Diabate, Cornell assistant professor of comparative literature, said the use of nakedness as a form of political dissent has proliferated since the 1990s. She has documented almost 500 collective naked protests around the world on globalization, capitalism, HIV/AIDS, war, power abuse, Black Lives Matter, animal rights, land disputes, environmentalism and even Donald Trump.

Diabate offered an example from 2008, when hundreds of Liberian women war refugees in Ghana demanded better relocation packages and mobilized what Diabate called “their most powerful methods of protest, the threatening exhibition of their genitalia, which aims to produce the social death of the men so cursed.” The Ghanaian government called the women’s public self-exposure “a threat to the security of the state” and arrested them, even deporting some to Liberia.

Despite the ubiquity of naked protest, Diabate said it can differ considerably in meaning and significance. To explore the epistemological and social problems of this universal, yet highly culturally informed, form of protest, Diabate advocates for worldly literary criticism, such as her analysis of Nigerian novelist T. Echewa’s “I Saw the Sky Catch Fire.” The novel reconstructs the 1929 massacre of Igbo women showing their naked buttocks in a collective genital cursing against female taxation, to horrified British colonial administrators.

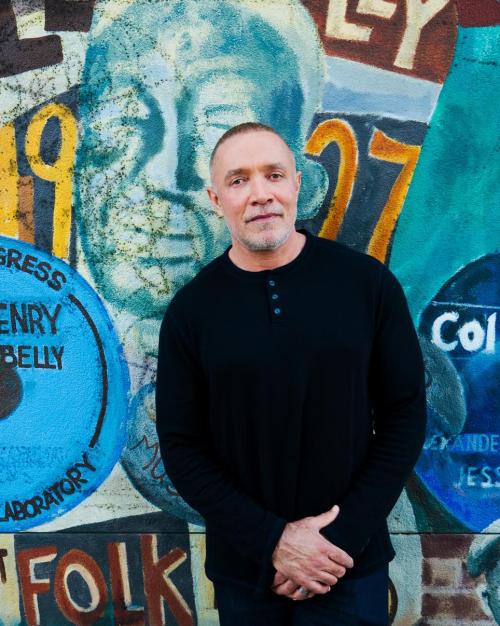

Ricardo Wilson II’s talk, “On Stone and Skin: Covarrubias and the Olmec Problem,” drew on his current book project, “Toward the Nigrescent Beyond,” which investigates the growing need in the United States to hide ideas of radical blackness within liberal and neoliberal discourses on race and culture, “a process of psychic vanishing that I argue is straining to dominate our collective imagination.”

Wilson, a Society for the Humanities Mellon Postdoctoral Fellow whose teaching home is with Africana studies, said he focused on Mexico because its “founding thinkers began to conceptualize it as racially egalitarian in its struggle for independence from Spain in the early 19th century; its imagined post-raciality, especially in relation to a vanished idea of its own blackness, has [thus] been seen to a certain conclusion.” Wilson discussed debates surrounding the discovery of artifacts related to the Olmec civilization in the 1940s, which were initially described as “Negroid in appearance,” launching a debate about the nature of Mexico’s indigenous identity.

That discourse, said Wilson, was “founded, primarily, on ideas of phenotype, which of course includes skin, and the accompanying notions of authenticity.” The rejection of any connection of the artifacts to Africa, said Wilson, pointed to a negation of blackness in Mexico’s collective conscience, which helped “to structure contemporary ‘Mexican culture’ and the nature of what radiates through it.”

The conference concluded with a choreographic piece on the history of cotton picking in Alabama by the dance group, The Low Mountain Top Collective, followed by a panel with current Society for the Humanities fellows.

This article was also published in the Cornell Chronicle.