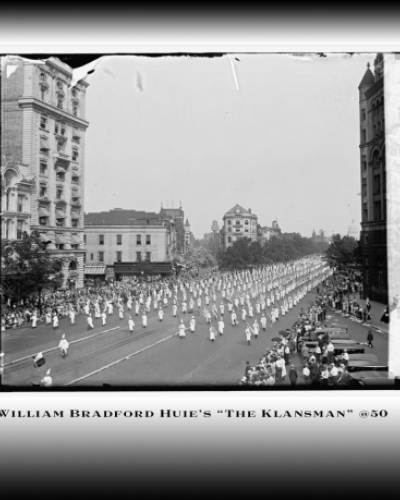

The rise of Donald Trump has thrust the Ku Klux Klan into the national spotlight. To better understand the true threat of the Klan and its history of violence and terror, it is crucial to return to work by civil rights activists of an earlier era, especially William Bradford Huie’s 1967 The Klansman. This novel, published 50 years ago, examines the dangers of the organization’s propaganda and its deadly consequences. It is important to pay attention to such critiques, along with more contemporary ones, to recognize what we can learn from them, even though this is such a hard subject to think about, talk about, and teach.

The Klansman reflects on race relations and sexual tensions in a segregated Southern town. Set in the fictive Ellenton in northern Alabama during the 1960s, the novel opens with the narrator’s heroic portrait of the height, weaponry, and family background of Sheriff Big Track Bascomb, a Medal of Honor recipient, so as to underscore his strength as a man. As the novel begins, Big Track and his 17-year-old son, Allen, transport a prisoner down to Mobile. Along their way they see photos of interracial fraternizing that allegedly happened during the Selma-to-Montgomery march in 1965, travel to the location where Viola Liuzzo was slain, and meet and take a photo with Governor George Wallace. Such elements give the novel the flavor of historical fiction.

The plot thickens when a young black woman named Loretta Sykes returns home to Ellenton to nurse her terminally ill mother. Breck Stancill, a wealthy white man who uses his wealth to provide shelter and sanctuary for local impoverished blacks, had bought Loretta a typewriter as a teen. Her talent typing helped her to migrate to Chicago, where she found work as a secretary at Montgomery Ward. Elmer “Butt Cut” Cates, the Sheriff’s deputy, mistakenly believes that Loretta’s reason for returning home was to work with activists, and wrongly presumes that she’d once been sexually involved with Stancill.

Butt Cut arrests her and, while Sheriff Big Track is away, works with the Klan to orchestrate her rape in the jail by an illiterate black man named Lightning Rod out of resentment of her education and career. The year before, tensions had been high after the Klan’s lynching of a black man named Willie Washington for the rape of a white woman named Nancy Poteet. As racial tensions in the area continue to intensify, Klan members attack Stancill’s Mountain and take several lives, killing Loretta and her mother. Big Track’s evasive investigative work of their deaths, Breck learns, is shaped by Big Track’s Klan sympathies and a clandestine membership in the organization. Breck attempts to persuade Big Track to expose the Klan for its role in the recent murders. Unlike his father, Allen publicly condemns and rejects the Klan, whose members kill the youth and Breck. The novel concludes as Big Track faces a federal arrest warrant for failing to protect the civil rights of Loretta, her mother, Breck, and Allen.

The work of prolific Alabama novelist William Bradford Huie allows us to look to Southern history and literature to learn crucial lessons on how to prevent the Klan from terrorizing this new American present. Huie’s The Klansman was revolutionary as a literary work and remains significant today for its critique of this organization and for several other factors. I will focus here on the novel’s antiracist model of white Alabamians in Breck and Allen, its critique of the damaging impact of racist Klan propaganda and the costs of buying into it, its radical model of black womanhood, and its implications for the Black Power movement. All of these dimensions not only made The Klansman a radical novel for its time, but also are part of why it continues to be relevant now. Read the complete article at Public Books.org